Interview: Daniel Vassallo: "Self employment is a game of taming uncertainty"

Daniel Vassallo talks about his journey from tiny island to high-paying US tech job to diverse "small bets" entrepreneurship, and what he's learned about the randomness of business along the way.

This is the latest in a regular series of in longform, in-depth, Q&A-style interviews on Fee Sheet. If this is your first time here, check out this post about what this publication aims to do, and this one about pricing. All interviews are posted on a 50/50 system. The first half — often several thousand words — will be available for free. The rest, and most other content, is for paying subscribers.

Now, on with the interview!

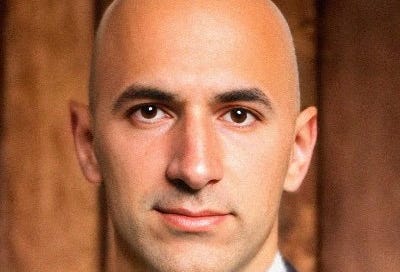

Daniel Vassallo is a US-based self-employed entrepreneur and former Amazon Web Services software developer who left almost a million dollars in Amazon stock options on the table to pursue the entrepreneurship path. He is the founder of Small Bets, a community and education platform that helps aspiring entrepreneurs and disillusioned employees alike to leave aside the dream of starting a billion-dollar company and instead try to make $1,000 with a small project first. As the Small Bets philosophy goes, “We learn a lot more from small wins than from big failures.”

In this wide-ranging conversation, Daniel discusses:

His early memories of computer programming and making money online

How high-paying tech jobs can become a heavy set of “golden handcuffs”

The challenges he experienced in the transition to self-employment

The lessons learned about randomness and uncertainty in business

How to approach audience-building and creating content online

His philosophy on goal-setting and maintaining motivation

Why “putting on a show” is essential to online success

And lots more

Shane Breslin: Welcome, Daniel. So as with all content on Fee Sheet, the central theme is money and finances. What are your earliest memories of money?

Daniel Vassallo: To be honest, I don't have many early memories of this. Growing up, my family never really spoke much about finances, and I was never particularly curious. I was never someone who hustled to make money or sell things. I was mostly into computers. My parents got me a computer when I was five years old, I got hooked, I started programming very early on, and for better or for worse, that's how I spent most of my childhood. Every bit of pocket money I got went on computer stuff — on new gear, on magazines to learn things, on upgrading my computer's memory.

“Much more than the money was the experience of doing something and then people from all over the world using it, that was the thing that was life changing about it. Malta is a very small country, surrounded by water. The Internet gave me that first sense of freedom.”

SB: We'll be talking a lot more about programming later on, but what about the first time you got paid for something. Any memories come to mind?

DV: It was when I was about 14 years old. We'd got the internet — this was 1996-ish — and I was programming during summer breaks, making my own computer games. And the web opened an opportunity for me to try other things. I tinkered with websites about computer games, but long story short, I had one website that grew a little bit, I partnered with an Australian guy, and we started putting some sponsors and ads on the site. I remember the first check of about $100 coming in the mail. It took over a month to arrive!

I wouldn't say the money changed my life, but the way I thought about things really did change. You have to understand — we lived in Malta, and Malta is a very small country, surrounded by water. The Internet gave me that first sense of freedom. I realized I could reach people outside easily, without needing to catch a plane. So, much more than the money, the experience of creating something and people from all over the world using it, that was the thing that was life-changing about it.

SB: What was your family background? Were your parents entrepreneurial, or did they work regular jobs?

DV: In the same way I was always interested in computers, my dad had always been interested in agriculture. In 1979 or '80, a livestock epidemic required all animals to be slaughtered, farms had to start from scratch and the government offered subsidies to do so. So my dad got started in pig farming. Our house was next to the farm, and he continued this until I was 14-15.

A bit of background here. Malta in the 1980s was in political turmoil. It was democratic, but it embraced a sort of pseudo-communism, nationalizing everything despite siding with the West. For example, the government decided the country didn't need more doctors so it closed medical schools. The government was aiming to make the country sustainable. Malta is a tiny island — 10 miles by 11, and a population then of around 300,000, with effectively no natural resources. And the communist mindset wanted to minimize imports.

Malta modernized in the late 90s, and it looked like it would join the EU. So this was going to be a threat to farming. Being part of the EU would require removing protectionism, and Malta couldn't compete with Italy, one of the world's biggest food producers. [Malta eventually joined the European Union in 2004.]

So with EU membership looming, my dad made a career change. He went back to university to study pharmacy, and eventually opened a veterinary pharmacy clinic and wholesale business, which grew to include pet shops and an animal hospital. So through this I gained exposure to entrepreneurship in my early teens. I wasn't very active in the business, but I absorbed information — concerns with employees, partners, different ventures, about successes and failures and all the things that happen in business.

“Self employment is a completely different game than when I was an employee. When you’re an employee, the game has very predictable parts, like a video game. You score points and level up. The game is about going through the levels.”

SB: You mentioned a $100 check you got from Australia. What was that for? What had you delivered? Who was paying that?

DV: It was for ads. There was an ad-serving company called DoubleClick, which Google later bought. We focused on football games, spinning up new sites as soon as new games were announced — ours was often the first site on the subject. We had some sites that were quite popular, 1,000 views a day, so we decided to place ads on the site. This was the early days of banner ads — there were banner ads on the top, sides, everywhere! The payment came from Australia because I partnered with someone there. He was 18, so he had a bank account, and he sent me my share in the mail.

I did this for a couple of years, balancing it with school. However, it became exhausting because it was very demanding. My partner had bigger ambitions, while for me it was mostly a hobby. Eventually, I lost interest as I wanted to focus more on my studies and other things that interested me.

SB: You worked for Amazon for a long time. Did that come about straight after college? How soon did you realize that the skills you were developing were becoming very valuable to the marketplace?

DV: I’d started a physics and computer science program at the University of Malta but dropped out and I joined a correspondence degree program with the University of London. Because that was all by post, I had time to work also, and I had lots of jobs during that time — in a school lab, waiting tables at a restaurant, QA for a winery, sales for laboratory equipment — but my first real programming job was part-time at a sports betting company in Malta. This was around 2005, and it was probably the first time I had that feeling that what I was doing was super valuable. Their developer had let them down and I went for an interview — I had a sort of “fake it till you make it” approach, but I knew I could help them. They were manually inputting loads of data. So I saw ways I could automate a lot of these tedious manual processes, which saved them hours of work every day. I continued there for about four years, transitioning to full-time while completing my degree.

After that, I worked for a company doing GPS tracking devices for vehicle fleets. This job allowed me to go deeper in programming, working end-to-end on a system that tracked vehicles in real-time. Eventually the company ran into financial difficulties and struggled to make payroll. I remember chatting with my girlfriend, now my wife, after two months in a row when I didn’t getting paid, and we said, “What are we doing here?!”

Malta had joined the EU by then so we could travel anywhere in Europe. Ireland was becoming a bit of a Silicon Valley for Europe, or that was my impression, so in 2010 we went to Dublin to get a look and feel, and we liked what we saw. So we took a one-way flight. We barely had two months worth of savings. We said to each other, let’s see what happens. If it doesn’t work out, we can come back and live with our parents until we get back on our feet.

I interviewed with several tech companies in Ireland — Google, Microsoft, Amazon and lots of smaller tech startups. There were lots of opportunities, but when Amazon came back, I accepted their offer. It was €55,000 with minor stock options, so not the most competitive, but I had an affinity for Amazon Web Services from my previous job so I jumped at it. A couple of years later, I was invited to move to Seattle, which is what brought me to the US in the first place. I ended up spending almost nine years at Amazon.

“Online, you have to accept that you need to ‘put on a show’. You have to focus on presentation. Presentation is almost more important than the content itself. You’ve got to find a way to make your content entertaining or engaging, or both. Every post you make should be designed to make people pause and think, or smile, or learn something new.”

SB: What was your approach to learning code? Did you pursue programming languages based on what you enjoyed, or were you judging them against what was needed in the marketplace?

DV: When I was younger, it was purely driven by fun. I wanted to make computer games, which led me to C and C++. This gave me a good foundational understanding of software in general. Later, when I started getting paid, my choices were mostly pragmatic — it was about getting the job done, using what was needed for a specific project or working with existing software in a particular language.

Programmers tend to be a bit religious about the tools and languages they use, but I saw myself as a generalist. Like an F1 driver who moves from Red Bull to McLaren or Mercedes and they just dive into the depths of the car and the tech. That was the way I looked at it. I was just happy to get curious about what the tech could do.

So my choices weren't necessarily market-driven. In a way I stumbled into this lucrative profession by accident. Maybe subconsciously, something in me never wanted to be struggling financially, probably since I was little. I realized it's important in life to have a cushion. I always had a strong desire to protect my downside. I just didn't want to struggle.

“Having money gives you optionality. It gives you the freedom to spend it how you want.”

SB: Where did that come from, do you think? That thought process that you wanted to protect your downside and avoid struggle however you could?

DV: It's hard to pinpoint exactly, because in Malta, despite its economic flaws, there was no extreme hardship. The pseudo-communist system had elevated the baseline standard of living.

It was more about the pursuit of freedom and optionality. Even with my pocket money as a child, I enjoyed the freedom to buy my own things. When I started working while my friends were still studying, I appreciated being able to afford a car, go on vacation, buy things for myself.

Having money gives you optionality. It gives you the freedom to spend it how you want. This attraction to optionality and the desire to flourish in life probably guided me subconsciously, but it was never a calculated decision to choose the highest-paying career.

It was partly luck that my interest in computers aligned with a lucrative profession. This wasn't obvious in Malta in the early 90s, as programming wasn't a well-known career path. But as I read magazines and learned more, I began to understand its potential.

“I’d gone from not really saving anything — not much more than paycheck to paycheck — to having a retirement plan, saving money, investing in the stock market. I bought a house with $200,000 cash down payment.”

SB: So you’re at Amazon, one of the biggest companies in the world. We hear lots about the legendary Jeff Bezos way. Was it an entrepreneurial environment? Did your time there foster that spirit in you?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Fee Sheet to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.